March 15, 1979

Picture #1 – First Band – The Oberlin Boys Band organized by Wainwright in 1913 took a trip to Washington. Wainwright is at the far right.

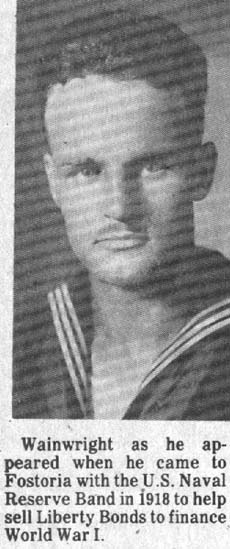

Picture #2 – Wainwright as he appeared when he came to Fostoria with the U.S. Naval Reserve Band in 1918 to help sell Liberty Bonds to finance World War I.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first in a series of four articles to appear weekly in this column about Wainwright

John William Wainwright was born in Lisbon, Ohio, on October 30, 1889. His parents Luke and Sarah Elizabeth (Bramleu) Wainwright, migrated to the United States from Heage, Derbyshire, England, in 1882 and were naturalized in 1888. The Wainwright family first settled in western Pennsylvania in the town of Clinton, Beaver County. Luke and Sarah Wainwright raised a family of 11 children, one of which died while they were living in England and is buried there. “Jack” as he was called throughout his life, was the eighth child in the family line. The Wainwright’s were deeply religious, hard working and poor in worldly goods, according to Mrs. Jack Wainwright.

The Wainwright family was musical and formed its own vocal and instrumental groups. Jack’s father played the ocarina, better known as “sweet potato”. The girls sang in the Methodist Church choir and the boys performed in the Lisbon Municipal Band. Jack was a trombonist and also played the nickelodeon. He was the only member of the Wainwright family to pursue music as a career.

At approximately age 16, Jack left school and worked at various jobs from banking to printing. He eventually pursued the latter in a Lisbon print shop.

He learned to repair and operate the linotype machine, wash the print forms, sweep out the shop and run errands to other print shops to borrow a “left handed monkey wrench” or a “type stretcher”.

He left Lisbon at about age 18 to accept a position in Galion, and in 1910 he accepted a position at the Oberlin Tribune to operate and maintain the paper’s linotype machine.

There’s an old saying that once printer’s ink gets in the blood you’re hooked. That must have been true with Jack Wainwright, because after he came to Fostoria to teach music and start the band he never completely got away from the printing business. Jack and one of his brothers had a print shop in the old brick school house that stood on West South Street at approximately the location where Mr. B’s is now. After he disposed of that shop he often come to The Review Office when this author was working there. He liked to see the action in the composing room, and to sit down at one of the linotypes if there was an opportunity. Often on election night, or when we were getting out “specials” he would turn out a couple galleys or type on the linotype. He also had a small print shop at his band camp in Indiana.

THE OBERLIN YEARS

During his academy years Wainwright became intensely interested in bands. The Country Gentleman Magazine printed the following story about how the Oberlin boys Band got started.

One day while operating his linotype, he (Wainwright) heard a band come down the street, went out to investigate and be held a picturesque aggregation of instrumentalists doing their poor best with a simple march. They had enthusiasm without equipment or harmony. Something thought Jack, should be done about this bunch, which is misrepresenting Oberlin.

Wainwright organized a boys band in Oberlin on November 24, 1913. Seventeen boys signed up and Jack became the director.

They secured the services of Harold Hall, clarinetist, and E.T. Thomas, flutist, to give instructions on those instruments. Wainwright gave instructions on all brass instruments and drilled the boys.

Instruments of all types were dug out of closets or borrowed or bought and the new band got off to a good start.

By May 30, 1914, 30 youngsters were ready to march and play in the Decoration Day Parade. Arthur L. Williams, a member of the band, and later a faculty member of the Oberlin College Conservatory of Music and director of the Oberlin College Band, and a one-time member of the faculty of the National Music Camp at Interlochen, Michigan gave this account of the Decoration Day Parade: “I remember well our first May 30 parade. We played two funeral marches which Wainwright had written specially for us. We alternated these while playing for the parade through the business section of town”.

PIONEER IN INSTRUCTION

Much of the success of the Oberlin Boys Band, as well as the other bands Wainwright directed in later years, was due to his pedagogical approach to training the band as an entire class rather than on an individual private lesson basis.

Wainwright was one of the first persons in the United States to discover that it was possible to teach girls and boys how to play band instruments in a class made up of absolute beginners on the various instruments at one and the same time. They learned to play in the band from the very first lesson.

Before this discovery, if a student wished to play in a band he had to take private lessons and practice for several years before getting in a band. Not many could be persuaded to practice the uninteresting “umps” of the tuba or the “pas” of the alto horn for several hours each day. Therefore, everyone who took up band instruments chose a melody instrument such as the cornet or trombone. With only melody instruments available a band was impossible. Thus, when it was found possible for students to play in a band from their very first lesson, there was no difficulty in having all of the instruments needed.

It is not known how many band leaders touched upon the idea of heterogeneous instruction and were using the technique in actual practice.

It was not until 1923 that Joseph E. Maddy and Thaddeau P. Giddings published the first heterogeneous method of teaching instrumental music, he also advocated private lessons to improve the quality of the band.

1914 SPECIAL TOUR

The Oberlin boys worked hard to improve their band. Wainwright told the boys that if they worked real hard and learn to play enough pieces for a whole program he would take them to Washington. Their efforts payed off.

Later in the year (1914) the Oberlin Boys Band, then numbering 24 boys, ages eight to 14, were selected by the North Eastern Division of Corn Growers to accompany the “1914 Buckeye Corn Special Tour” to Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and New York City. The other band was the Risingsun Girls Band. The trip was made possible when the State of Ohio assumed one-half of the cost.

Mrs. Jeannette S. Wainwright, wife of the late Jack Wainwright, compiled the following excerpts from old scrapbook clippings about the 1914 tour.

WASHINGTON-PHILADELPHIA

The tour group numbered 1,067 (one account said 2,000 adults and young people, many of whom were prize winning corn growers). Numerous officials including one congressman-elect were with them, and Governor Cox (Ohio) was present, at least in Philadelphia, where he made the response to welcoming addresses.

They required five special cars and were transported over the Pennsylvania Railroad. They left Cleveland on Monday, Nov. 30. Tuesday and Wednesday were spent in Washington, D.C., where the band played a concert for President Woodrow Wilson on the steps of the White House. He gave a reception for them and shook hands with each one.

Arriving in Philadelphia Dec. 3, a representative of the mayor greeted them at City Hall. They had dinner at the Bellevue-Stratford, then there was a theatre party at Keith’s where the band played a concert. They then boarded an 11:30 train for New York City.

BIT HIT IN N.Y.

In New York they were greeted by Mayor Mitchel. Dinner was at Hotel Martinique. The event best remembered was their concert at the Hippodrome that evening. While they were playing all the lights went out; but those boys knew their numbers so well that they kept on playing, which brought down the house.

The last evening of the tour was described in a story in The Oberlin Review (Dec. 11, 1914), headlined, “Saw the Band Boys in New York”.

Cushman Carter, and I went to the Hippodrome, and from our seats in the second balcony we looked down into the first box, and there was Jack Wainwright with his 24 little band boys. Between acts they favored the 5,000 or more people with a piece; then the little Williams boy played his famous cornet, solo. It sounded fine and made a great hit. After the show we hunted them up, and marched proudly beside them as they paraded down Broadway and Seventh Avenue to the Pennsylvania Station. The big traffic cop cleared the way for them as if they were the crowned heads of Europe.

BOYS BAND POPULAR

Following the “1914 Buckeye Corn special Tour”, the Oberlin Boys Band played concerts in many communities in northern Ohio. Wherever the band played Wainwright would announce that any parents interested in forming their own community boys band should meet with him after the concert. Consequently, Wainwright organized bands in Elyria, Lorain, Wellington, and Berlin Heights.

AT OBERLIN CONSERVATORY

In 1914 Wainwright entered the Oberlin College Conservatory of Music at the insistence of Professor Karl W. Gehrkens, who was impressed with the work he had done with the Oberlin Boys Band and his group training methods.

Wainwright as a student in the Conservatory also taught many of the wind instrument classes there. Some historical date says that he was either chairman or head of the wind instrument department, althoough records at Oberlin College show no evidence of his official appointment to the position.

In 1914 Wainwright assumed directorship of the Oberlin College Band a job he had held until 1918 when he enter the service.

ENLISTS AND WEDS

In the spring of 1918 Wainwright enlisted in the Naval Reserve Band in Cleveland.

In August of 1918 Wainwright announced his secret marriage of Feb. 2, 1918, to Jeannette E. Streeter of LaGrange, Ind. The announcement in the Oberlin News revealed that Mrs. Wainwright was a graduate of the Oberlin College Conservatory and would be teaching at Wooster College, Wooster, the following year while her husband was in service.

In the Naval Band, Wainwright became assistant director of organization to H.L. Spitalny. The band toured extensively promoting the Liberty Loan Bond drives.

BAND COME TO FOSTORIA

During the month of October 1918, the Naval Reserve Band traveled by Nickel Plate train to Fostoria to play a concert and promote the Liberty Bond Campaign. When the band arrived Wainwright asked a trainman the name of the town. He replied, Fostoria, and Wainwright replied, never hear of it.

Little did Wainwright know at that time of the opportunity Fostoria held for him. The concert was given in the Fostoria High School auditorium under Wainwright’s direction and was extremely well received. F.H. Warren, superintendent of the Fostoria Public Schools and a lover of music and the fine arts, was impressed with the band’s performance.

Years later, when Wainwright and his Fostoria High School Band won the National Championship Award at Chicago in 1923, the following information came to light and was published in The Review.

Wainwright made an impression on us when he came to Fostoria in 1918. He told me after the war was over he would like to come to a new town like Fostoria and start a new band. Jack looked like he could do anything he wanted to do so I told him to get in touch with me after the war, said Supt. F.H. Warren.

Wainwright told him (F.H. Warren) that it was his dream to see some day, every high school in this country with a band equal to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station Band, and to have every school child familiar with a musical instrument, reported Mabel Bourquin, a Fostoria High School English teacher.

WAINWRIGHTS LEAVE OBERLIN

Wainwright was discharged from the Naval Reserve Band in December 1918. The Oberlin Tribune reported Wainwright and his wife planned to make their permanent home in Oberlin. However, Wainwright must have acted quickly in contacting Fostoria’s Superintendent Warren, because a little later the Oberlin News announced that the Wainwright’s had left to make their home in Fostoria.

WAINWRIGHTS IN FOSTORIA

By February of 1919 when Wainwright, his wife, and new infant daughter had settled in Fostoria, he had worked out many of the details of organizing the Fostoria High School Boys Band. He had presented his plan for an instrumental music program in the schools to the Fostoria Board of Education on Jan. 16, 1919. He would organize the students of various ages and grades into classes, and teach them instrumental music for $3 per student per month. In return, Wainwright would be given a classroom at the school where he could teach. Agreement was reached to the plan. The Board of Education, however, placed two restrictions on the plan (1) music instruction must not interfere with school work (2) rehearsals were to be conducted after school hours.

At Wainwright’s only compensation from the school board was the use of a classroom to teach in. In return, he was to conduct band and orchestra rehearsals.

Wainwright went to the C.C. Conn Company to purchase instruments for the band. He convinced the Conn Co. of the soundness of his idea for building a band, using an instrument rental plan. They agreed to sell him a large number of instruments on a long-term deferred payment plan.

Mrs. Wainwright related the following about the rental plan:

The expense of providing instruments for pupils was colossal and we were never out of debt. The pupils were to pay monthly rental, also for the instrument repairs. At first the rental was #3 for violins, more for brass and reeds, and $5 for saxophones. The fee included a private lesson a week. Jack wanted it understood that his plan was not a scheme to sell instruments, but simply to provide them so that the band and orchestra could be developed. Students received a reduction in the price of the lesson if he bought or provided his own instrument.

Students with talent, but without the financial means to pay were provided instruments and lessons. In return for the favor, students worked, helping to repair torn music, setting up chairs and stands on the stage for rehearsal and concerts, and loading instruments and equipment on trucks for trips.

It was truly an awesome and staggering program that Wainwright set up to provide instrumental music and a band for Fostoria. But the lack of money didn’t stop him. He borrowed money to meet Conn’s payment plan, and then, when he didn’t have the money it is said he would dodge his debtors when they came to town to collect.

INSTRUMENTS ARRIVE

The first of the band instruments arrived in February 1919. Henry Spooner recalls that he and Duanne Harrold, both in the early band, went to the Wainwright’s house to pick up their trombones. It was the large brick house that still stands on North Main Street across from the Credit Bureau and Two Guys Barber Shop.

At the beginning all work was done in classes, but boys were promoted to private instruction as soon as their progress warranted. Most of the class work consisted of work with scales and rhythmic patterns, the classes being made up of 10 to 12 boys, with no particular regard to instrumentation.

There was a set rule that music lessons were not to interfere with school work but three former band members, Ernest Duffield, James Guernsey, and James Carter, all agree that they often left classes to attend lessons, and special rehearsals.

One month after lessons started the first recital was presented. Teacher, Mabel Bourquin reported It is safe to say that every seat in the audience held a skeptic, especially among the local musicians. These recitals are regular monthly affairs throughout the winter, enabling the pupils to appear singly, and in ensemble work. No exercise is too trivial, if it is well played, for the pupil’s first appearance.